“On his shoulders bore the gates of azure.”

-Samson Agonistes, Milton

Singing Giants sounded down the pass from Tiger Mountain, down the mountainside from Cedar Mountain, up the cut from Green River Gorge, and up from the sea. The south and north wall were built, the men cheered by the sword glowing under the wendigo hide, but not willing to work on that gate of the north wall with it there.

The work stopped at noon with those great songs, hoots that carried from mountain to mountain, trees beaten like drums by logs held to some inhuman hand. The snow no longer drove. The day was clear, cold, sparkling under heaven, the creek frozen solid, the river freezing below. The cattle could not gain the feed below the hard frozen crust of snow.

Thirteen was felling and sliding the last of the timber up on the south face of the saddle, sliding those great trunks down the mountain. Tomorrow morning they would all be hauled by the steer teams to front the fort.

“Two walls done, Son,” said Peter Grim leaning on his long iron pry bar. But there is no feed for the cattle, the oats all but played out. Cut out the weakest steers for to slaughter and smoke.”

“Yes, Father,” as Peter headed down to the river with pistol and whip to drive the stock back up to the fort. How he missed his hounds, lost with his brothers, to wolves and worse over this past year of winter. Father’s voice, low and grave, came to him, “Then the calves. We will need what milk we can to make butter for spring. The beef won’t last the winter.”

‘If winter ends,’ groused Peter in his forested mind, having learned much from the silent wisdom of the cedars.

Peter nodded to his sire, the both evermore sad than the moment before. What hay and oats were left had to be reserved for the horses. The cattle, except perhaps the choicest cow and strongest bull, would not last the winter. If they could be let range—if there were no polar bears, wolf packs and worse driven south to ravage them, they were not bison and would be unable to endure the coming cold and get to the feed below the snow.

In a few minutes, down by the river, Peter found himself driving the last stubborn bull before him, up the hill, cracking the whip, as two dozen elk looked on from the river bank, sadness in their eyes. He stopped and looked at the lead cow and the bull, as well a lesser bull who was keeping alongside the herd bull. This younger bull had a flap of hide hanging from its flank, trailing blood as he used his rack to brush snow aside for feed. Those creatures that had ravaged him, and had deprived the entire herd of calves, were not monsters risen from Indian tales, but a pack of wolves, who eyed Peter, looking across the river at him with cold gray eyes.

‘I’ll not watch them take this bull, or the last elk in this range.’

Peter looked away from the wolves, laid off whipping the bull, belted his pistol and whip, unslung the rifle from his back, cocked it quietly, raised it to his shoulder, turned, sited the pack leader, and fired. With a crack and a yelp, the alpha male went down on his haunches with a 0.50 caliber slug through its hips. It whined, as did its bitch.

Peter recharged his rifle, began to drop a ball down the barrel and draw his ramrod, and they were off, up the pass to the northeast, howling, the lack leader dragging behind, the young bull prancing over to gore it down, then stamp out its snarling brains.

‘They will have a night to reorganize. By morning they will be back. Allies with elk, now, prey like they?’

The giant songs stopped for so long as it took for the pack to gain the mid point of the pass and their howls to fade away. Then their songs came again to oppress the day. By the time Peter was reloaded, Thirteen was slapping the bull on its backside and shewing it up the way like a slack hound.

He came to Peter with crunching steps, stood to the northwest of him, his shadow casting Peter in a singular frame, to whisper, “Master, see you the top of the pass,” and handed Peter Father’s spyglass, who had insisted the tutor logging on the saddle of the mountain apprise himself of what lurked on the ridge lines and peaks. For the great sword that had slain the Wendigo was guarding the fort builders, its glower spying the wendigo by night, but lacking the contrast to do so by daylight.

From under cover of the knight’s shadow, Peter looked to the old bight of naked rock that was the peak of Tiger Mountain, far above the pass where the moaning wolves retired to. Peter gazed at the west slope, topmost, among a clearing at its base, where the cliff face permitted no trees, and below which Father had once cleared a signal station, a line cabin, from where his brothers were one by one lost. The cabin was being occupied by a number of Blackfeet who sat smoking outside of the cabin, smoke beginning to rise from its small chimney.

“A party of Blackfeet, maybe 30, maybe sixty, no more in this blow, maybe more back down the pass. I see Yakima guides, two—that is strange.”

“Above that, Master.”

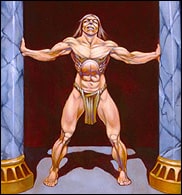

Peter scanned vertically to the very top of the pass and saw movement. Focusing the lens with the navigation dial on its end, he saw two figures, large harry ape-like men, each holding a small log, taken from a maple tree, cut, not splintered.

“I’ll be, Thirteen—thought they were a fable until January last, what the natives call Sasquatch, but, wearing shingles, I suppose, two of them, beating a cedar I know to be ten feet wide at the base, like it is a drum, making them over ten feet tall. They wear some kind of head gear and belts too. The Injuns have always described them as entirely undressed and unequipped. Look out, thirteen, they’re bigger than you.”

“Yes Master, a rider approaches, up from the sea, the horse faltering.”

Peter handed off the spyglass and made his way down to the river trail. Up the trail rode Tory Ball, the youngest and thinnest son of Jon Ball. His Manchuko warhorse, if it had been of any other breed, would have been blown. Its gray and brown shoulders were in a lather, its eyes wide with fright, its rider drawing a pistol and shooting behind.

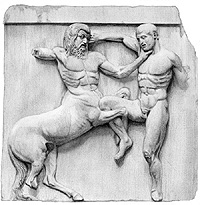

“Whatever is he shooti—I see,” halted Peter, raised his rifle, shouldered it, sighted behind the horse’s haunch upon the hideous, goatish ape-man running on cloven hooves and knuckles. With a breath and a prayer, ‘By God,’ Peter fired. The fiend spotted red from its splotchy gray hide, clacked its bear like jaws in its boar like snout in a gurgle, pressed its malformed hand of leather to its bleeding barrel chest, and lurched off moaning into the ferns, behind a great trunk.

Thirteen began striding down, drawing his arming sword, and Peter commanded, “No, he is a good rider. He will make it this far. Cover our approach while I reload. Father is headed down for a certain.”

“Yes, Master. Sound tactics. A knight’s heart calls.”

Tory Ball’s ride ended with the horse bursting its heart before them. The man was unable to speak from fear. Men were running down the hill in force.

Two more wendigo drew up just out of range, cracking their jaws loudly and snorting like tusker boars, then screaming like billy goats.

Peter handed Tory to Father and said, “Take him up, Pah. Thirteen and I will cover you, no time to collect the horseflesh in case this is a ruse to draw us down.”

“Yes, Son!” laughed Peter Grim.

Thirteen unhitched the saddle and shouldered it like a shield, the both of them backing up the knee deep snow of the pasture as more wendigo collected below and took up a hideous hoot, the drums and Sasquatch songs on the mountain tops waxing louder.

By the time they were back before the Cherub Ward, the wendigo were tearing at the horse and the wolves were howling above, as the elk, panicked to crazy, followed them up the mountain and stood grazing under their guns at the unbuilt north wall not afraid of the cold humming sword at all.