“James, have you written anything about Spartacus? I am currently teaching history and have my students watching the 1964 Kurt Douglas movie. I realize there are some inaccuracies. But the spirit of the movie, of the fight for freedom, is powerful.”

-White Monkey

…

The best book is titled the Spartacus War by a man whose name, is, I think, Barry Strauss. The hard back has a white dust cover. I also read on the subject in a number of general histories of gladiators and in Roman history, either Plutarch or Appian. Varro and Sallust are sources I have not read who are cited on the internet searches. Note that even when one prompts for ancient sources, mostly modern summaries appear. Here wee are, in the world Spartacus fought against, where the past is for sale and truth has a high price.

I have been enthralled—that is right, mentally enslaved—by the Spartacus notion of freedom against the machine since seeing the movie with my father on a Saturday afternoon when I was about 11, just starting to grow a mustache and get aggressive.

Aspects of Spartacus that I find of note are as follows.

Ethnicity

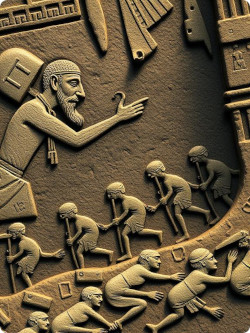

He was a Thracian, which places him as ethnically Arуan from the semi-barbaric reaches above Greece where the Agrianes hailed from and from whence a son of a slave, Diocletion, would be raised, under threat of death if he refused, to ruler of all Rome. The Roman Republic fought two or three Thracian Wars to subdue the region. Like the German chief that led the slaughter of Varus’ three legions in A.D. 9 in the Tutoberg Forest, Spartacus seems to have had experience as an officer of Thracian auxiliary troops, turning his knowledge of Roman methods against his captors. The fact that this zone, what we call The Balkans, would provide numerous bootstrap generals and emperors for Rome as She declined is of worthy consideration, speaking of peoples who may be politically conquered yet never abandon the notion of autonomy to some imperial machine.

Faction

Spartacus rose to command an alliance that included the Gauls of Crixus and another barbarian gladiator. Having won 8 battles, he was to lose the ninth as his force had split due to faction. This was a problem the Romans had as well, with much of the lack of success in rounding up the gladiator/slave army being related to the factionalism of the Roman government at the very top. Julius Caesar, Crassus and Pompey, the men of the Triumverate, were maneuvering for power at the time of this rising. The very pirates that had captured Caesar, would betray Spartacus, probably for payment, and eventually be hunted down in their own time. Histories tend to focus on the rebel lack of unity. Yet the rebel leaders actually worked together better than the imperial Roman leaders.

Religion

The Spartacus rising was the last of three massive slave rebellions put down by Rome over a hundred year period. Part of the problem was that entire tribal and civilized militaries were enslaved, including leaders. This enabled mass uprisings. A Sicilian revolt of hundreds of thousands, included a prophet who prayed at the volcano of Mount Etna. Trajan, 150 years later, would remedy this by having the Dacians butchered in the arenas as civic sacrifices, rather than putting them to work. The long term solution of Rome would be to invite second tier conquered men into the Roman power structure, to accept Roman Civic Religion, citizenship, which was about adopting a macro identity of success via scale. Spartacus taught the lesson to Rome that internal ethnic factions may result in faith-based revolts. Strauss explores implicit and explicit evidence that Spartacus was allied to a priestess of a Thracian cult, possibly a woman of the type of Alexander’s mother Olympus.

Of interest, is that in the future, significant revolts within the system will be religious, such as in A.D. 71. The various Hebrew, Pagan, Gnostic, Christian and Schismatic religious purges that featured hundreds of thousands slain in days or weeks in pure faith fervor, with no attempt made to topple the system. This internal strife enabled the system to remain as a great and increasingly hollow macroparasite, its inner reaches howling with religious rage. Henceforth, under such a system, as Christian Civic Culture evolved into an alternative, underground state, eventually to emerge as the new state apparatus, Rome implemented what I call the Spartacus solution. The weak will and low ability of Roman generals continued as a feature of the slavish gangster system. As Rome continued to gobble small tribal nations and absorb tribal refugees from barbarian population booms, the frontiersmen, such as the giant Thracian Maximus, and the sons of slaves scrappy enough to earn their freedom under the oppressive Roman system, began to emerge in the ranks of the legions. Rather than condemn these men to the arena or the mines, men like Spartacus were forced, at sword point, at threat of the extermination of their family and friends, to accept the ultimate scapegoat command, to become Emperor. Ultimately, the religious urge of the men drifted from the state, through the miraculous success of these doomed personalities, almost all of whom were murdered, into the ultimate cult of sacrificial, savior personality, to Christianity. The rise of Christianity as a martial faith that vested men of rival tribes and tribal legions with a unifying moral faith seems to have been predicted by the alliance and perhaps marriage of Spartacus with the shadowy priestess. Long before him the prophet of Mount Etna inspired the army of a Greek rebel general. The Spartacus slave army was logistically strong, had internal civic organization and was a risen nation, including tens of thousands of women to do the common chores that the Roman fighting man must do for himself. Men such as Constantine, would have similar relationships with bishops, who were very feminine figures, usually trained and served by eunuchs [tranny intellectuals] and fanatically wedded to Christ as a celibate male wife.

Heroic

To my mind, the most important thing about Spartacus was this, his direct honor. In his last battle, when his army of freed slave faced off against first class military legions, headed in person by Crassus, richest man in the world, Spartacus cast himself as a die. He went for Crassus, who was on the field, behind his men. Spartacus was met by three Centurians. This indicates that the common soldier of Rome was refusing to fight him and insisting that his bosses take the risk. This was the same thing that won Alexander his battles against the money men, that the slave soldier forced into the ranks insisted that his free or slave master fight the enemy master. Spartacus cut down two of the three centurians, the third killing him. The cause was lost. In the future, if a Spartacus was found, the money men had him posted to the frontier, poisoned or promoted to Emperor and murdered whever he began wondering where all of the sacred teasures dedicated to God had disappeared to. This was echoed in 1783 when Washington’s men plead with him to be king, to break away from the money men and lead the common man. Old George was no Spartacus, no Agricola or Gemanicus, to be murdered by agents of his backers. He kept faith with his money masters and turned his refusal to stand with Mankind against Money into an act of apparent grace rather than a hero’s ultimate disgrace.

It is my opinion that the rebel is always morally right.

It is my observation that the rebel always loses, because he fights against money, the fabric of which this world is woven—the rebel is a spider fighting against his own web, who does not realize he is doomed until that point when he discovers that he did not weave the web as he had thought, but was there treacherously led.

Spartacus was led around by his “wife”, a Dionysian priestess. The cult of Dionysus was a feminist and homosexual cult of degenerates who used drug-fueled orgies to provoke participants to acts of insanity.

The “slave army” of the Third Servile War made no efforts towards political reform. It consisted of multiple bands of non-Roman bandits who roamed around the Italian countryside looting. The reason it took so long to repress is that the Roman Republic was not yet prepared to behave like an empire. Former slave revolts had occurred in Sicily, not the mainland. Spartacus was not tactically brilliant, he was just the figurehead of a mob of drug-crazed degenerates who had no plans for the future and were thus unpredictable. Once Rome raised an actual army designed to put down the banditry, it was over.

The whole Spartacus thing is a lesson in what happens when a state imports a large number of ethnically diverse helots without the Spartan-style police state to maintain order. Which is what Crassus’ crucifixions ultimately imposed.

If you’re talking about the homosexual-coded Hollywood movie which justified violence for the so-called “civil rights” movement, then yeah sure that’s a good movie. If you’re talking about the actual historical Spartacus, then no.

You also have begun promoting a very degenerate and defeatist attitude which you need to stop. You keep saying that “rebels” against the money system always lose. No, those aren’t rebels. People who fight against the money system implicitly accept the system. That’s not rebellion, it’s a temper tantrum by losers. Real rebels don’t “fight the system” at all, because they live inside an entirely separate world. The religious martyr who dies for his faith is not rebelling against the money system because it has isn’t fair and prevents human flourishing. His act supersedes the entire premise that the material world has any say at all over his spirit. The real rebels are those who don’t fight the chains of materialism, they simply ignore them. One of the Richard Barrett posts you linked mentions this idea of putting something else at the center of your life. Rebelling against the money system is still just putting the money system as your focus.

That attitude is seen a lot in Christian martyrs, but also in other traditions like Zen Buddhism. There are many teaching stories about, for example, a Zen monk who is put in prison and chained, and someone comments on how unfortunate it is that he is chained up, to which the Zen master responds, “What chains?” At which the interlocutor is enlightened.

(If you are someone who seeks spiritual enlightenment by sitting in the same position for days while fasting, being put in prison on a starvation diet just makes your chosen existence easier.)