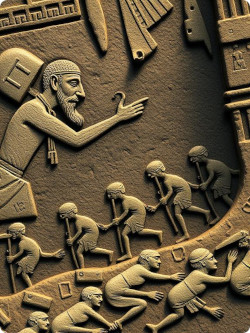

Milton, writing in the mid to late 1600s, penned his masterful works at the very time that same-race and English-over-Irish chattel slavery were shifting into high gear. Tens of thousands were shipped into oblivion annually, with 10,000 kidnappings alone claimed by one pamphlet circa 1680. As with Bunyan and Alsop, his contemporaries, Milton provides the poetic, and naturally more accurate view of living conditions for the literate person. That person existed, for the most part, one misstep from slavery, just as Alsop felt that plight. The reader of poetry is presented with things commonly thought true by he and his fellows.

Samson Agonistes is a poetical play script, following the blinded and shorn Judge of Dan in his agony and toil under the whip of his enemies, the Philistines. He spends the first act maundering on his own, is then approached by neighbors, his traitor wife, his father, a philistine hero, and finally an emissary of the Philistine King who holds him. The entire brief play seems to have been crafted, for the consideration of the young officer class, to teach him restraint in dealing with women, and suspicion of dealing with organized aliens, or outsiders. This period saw much political and military friction between Milton’s England and the Dutch. This was the period of Cromwell’s theocratic Protectorate, during which Dutch-based slave traders were invited by the Head of State into England to round up and sell off the poor, the debtor, the landless and the orphan. Samson is very much a half-orphan on earth, having been born of God’s own seed and raised by an earthly father.

After nine considerations of the two hour audio recording, I mark Milton as having tried to reform the dissipation of the officer class and to warn poor and illiterate freemen that bondage was one pitfall away. It was uncanny how much of Samson’s agony reflected the suffering of the bound multitudes of Milton’s own time.

As a play had appeal to the illiterate as well as the reader, I suspect that he was reaching for the mind of the unlettered Christian treading the precipice of sin all around in devil-haunted London, which Bunyan likened to the Jerusalem that betrayed Christ, and its folk who betrayed Samson before him. He also seems to have been warning the man with a few coins against vice, as drink and women were English methods for putting a man in bondage, whether a mother or sister sells him, or if he is sold off due to his last coins being spent on wine, women and perhaps on admission to Milton’s play. Having no coin and no master, was enough to bind out a man for a one way trip to The Plantations.

“Exiled from light,” from “a life heroic, this great deliverer now,” waned “lower than a common bond-slave, in a common workhouse,” suffering in self-critical agony, “not trusting women,” refraining from a quarrel with God’s will, damned by his bad choices, “blinded… worse than chains, dungeon of beggary—the vilest here excel me… in power of others, never of my own…”

Samson, in soliloquy, and in dialogue with visitors, hates what he has become in his fall, “Myself, my sepulcher, my moving grave, life in captivity among inhuman foes…”

A fellow observes Samson’s plight, “The dungeon of thy self, thy soul.”

Samson smolders at his past weakness that placed him here in abject meekness, “Gave up my fort of silence to a deceitful woman, by thy vices brought to servitude, bondage by ease…”

The question of God’s will is discussed and the fact of Atheists among them is noted by one, as “a school” uncredited with truth, “except in the heart of a fool.”

Samson wrings his soul, “She sought to make me traitor to myself, foul effeminacy held me yoked a bond-slave, true slavery.”

Samson’s father, in a manner of supplication similar to Priam seeking Hector’s body in the Iliad, seeks “to work his liberty,” through payment.

Samson responds in wise that any Englishman would understand, that lower forms of labor and the consequent diet are lethal, “Let me drudge and earn my bread until draft [work] or servile food ends my days.”

He rues his former glory, which has cast him in such relative pity, “Heads without name no more remembered… the ungrateful multitude… just and unjust alike both come to evil ends.”

Samson’s traitor wife comes to him and discusses her love of him conflicted by her loyalty to her Philistine kin and their god Dagon, wondering should “God be lord or Dagon?”

Samson grimly observes that if, “Dagon [is] entering the lists with God,” that he will be defeated, just as Samson slew many of his followers. This comes off as a warning against marriage to a non-Christian woman.

Delilah yet wants Samson home, her blind husband, to keep in house, pamper and care for like some pet. She pleads female weakness and that under her care, “they would only hold, not hate him,” expressing the institution of marriage as a hostage system.

He rages, “My wife, my traitoress… the contradiction of their own deity, gods cannot be. He moans that his blindness as cast him into, “Perfect thralldom,” that she has taken “the gold of matrimonial treason.”

She counters that she only thought her people would bind him, not blind him. At last, her rage rises, and she turns her back on him, leaving off with her train of slave women in all her beauty.

He snarls that, “Fame is not double-faced but double-mouthed.”

A hero of Gath, a Giant, comes to heckle Samson in his bondage, “Whose god is strongest, thine or mine,” indicates that at the start of the Plantation Period, Christians still entertained the idea of heavenly rivals to God, where at the close of the period, there remained only an idea of One God, challenged only by the ideal of Man as a self-generative god of works. Samson challenges the giant to fight, even in his fetters.

But the giant coward claims his right not to entertain a slave as a worthy rival, “A man condemned, a slave enrolled,” expresses the document-binding nature of slavery in Milton’s time.

Samson pines for, “my deadliest, my speediest friend,” being death. At this time thousands of English slaves drowned themselves in misery rather than serve under the lash.

“So debased with corporal servitude,” translates to working under the whip.

The Philistine emissary twice invites Samson to their agon in triumph of victory over him.

“Our slave, our captive, at the public mill our drudge…”

Samson, at last, agrees and pulls down the palace on the heads of the mighty and rich, the poor escaping as they had to stand out in the sun to view his humiliation, their low status saving them from God’s avenging hand. And Samson, the object of their heroic fascination, embraced, ‘Death who sets all free.”

Milton, who understood ancient faith so well, and its link to Early Modern England, crafted a masterpiece that would appeal to to pious Christian slave masters, and to their slaves, whose religious observances were limited by poverty and their faith eroded by cruel slavery under Christian and Non-Christian hands, according to tradition, a slavery sanctioned by the same wrathful God who redeemed Samson, even in his chains.